We're in deep: why do we cling to the things making us sick?

Business as usual is a sinking ship. We have to jump.

It crashed down in Budapest.

The rain, I mean. My illusions, I mean.

I lay in a grimy student dorm bed in Hungary while the wind beat down on the window. Turbulence.

My hand on my wrist counted the beats. Spotify techno mix on replay. I have played it since I arrived. Is that weird? My head is pounding.

I’m ill, obviously.

Whatsapp notification lights up my phone. Remember that we meet tomorrow at 7.30am so we make the lectures on time!!

I signed up for a summer school here, you see. I got on a bus and a train from Belgium to Budapest. 26 hours. Yes, it’s long. The time does not bother me. When you’re between destinations, you are nowhere and nobody. I like it.

But I knew, I knew as soon as the train started winding through Austria that I should not have come. You know that tiredness that comes with your body fighting off a sickness? I could feel it but I ignored it.

Mind over matter, I just need another coffee, and other lies I told myself.

After all, I’ve done it before, I reasoned with my imaginary audience of critics in the bus window. Slow budget travel and dubious decision-making is nothing new to me. It will be fine. Isn’t it always fine in the end?

But after a day exerting more focus on simply staying awake rather than following any of the lectures, I knew heavy in my chest I was doing it again. Falling ill and worse (to me): falling for the cognitive traps that we all like to think we’re too smart for.

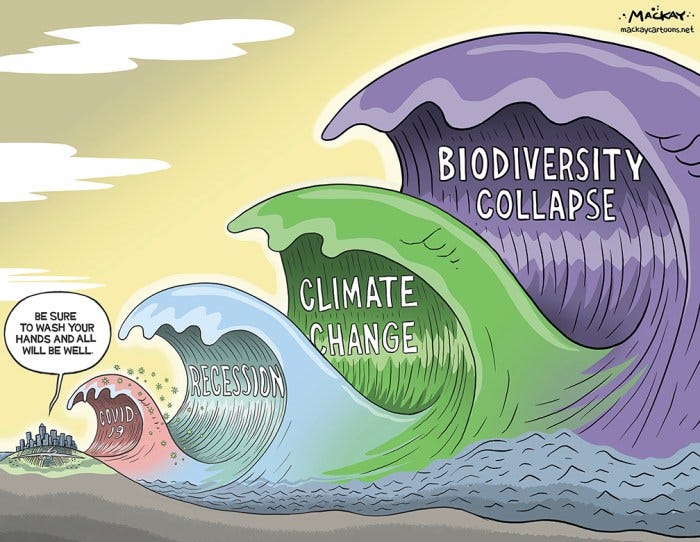

Ever wonder how politicians and neighbours could dismiss rising tides, killer heatwaves and melting Arctic ice caps and continue to put the climate up for sacrifice?

A heady cocktail of the sunk cost fallacy (I’ve spent X amount of time and money on this, I can’t give it up now) and normalcy bias (this disaster hasn’t happened before so it will probably never happen) makes us cling tighter to the things making us sick.

Like capitalism and carbon emissions and chronic overwork.

Haven’t I done the same? Ignored the warning signs, the spinning head and fatigue in increasingly narrow-minded pursuit of another line on the CV, to prove that There Was a Point to spending 16 hours twisted in a pretzel shape on a Flixbus and It Is Fine, Everything Is Totally Fine.

We all secretly feel that we’re immortal. Me most of all. Disasters happen to other people.

We cling to the illusion of a status quo like passengers on a ship slowly sinking. If it takes too long to go down, sinking becomes the new normal and we forget we will eventually drown. After all, we’ve never died before so why would it change now?

But who would want to live forever here? Who would want this ‘normal’ anyway?

Reader, lying on that dorm bed feeling too grim to even go out and sight-see, I quit the summer school.

We do not need to get used to suffering and just-about-surviving. When everything is is abnormal all the time, we can choose which brand of abnormality we adapt to. We do not need to stay burnt out and ill. I do not need to stay sick in Budapest.

Truth be told, we never needed any of this destruction at all.

Imagine getting used to freedom. And to having time and clean air and clean water. Imagine trees everywhere. That would be abnormal, at first. Freedom is a terrifying ambiguous beast - but it is far better than the beast we already know.

I could get used to the terror and exhiliration of a new greener freer world. I guess we’ll have to. Guess the status quo was the sickness and leaving it behind is the cure.

***

The Green Fix is taking a short pause for the summer and will return at the end of August.

If you like this newsletter, please help me by sharing it using the button here:

What’s Going On?

Shell estimated to make hundreds of millions trading Russian gas since the Ukraine invasion.

Related: War in Ukraine could hold back transition to global low-carbon economy.Eating less meat 'like taking 8 million cars off road', new study says.

Related: Big meat companies lobby to hide their damaging impact from major climate reports.Fossil fuel companies are using British influencers to go viral.

Related: How polluting companies successfully greenwash and how to fight it.July 2023 is the hottest month ever recorded on earth and yes it’s climate change.

Related: 6 places around the world using sustainable heat solutions.Climate litigation has exploded, but is it making a difference?

Related: Climate leaders need to model real accountability.

Is this newsletter worth a coffee?

We make about 10 euros per edition of this newsletter and it takes approximately 10 hours to create. We are volunteer-led and rely on reader donations.

If you want to support The Green Fix, you can tip us a virtual coffee.

Focus On… Deep-Sea Mining

Alexandra Vazquez-Mera talks to Deep Sea Conservation campaigner Sofia Tsenikli on why the ocean negotiations in July are a major deal for ocean biodiversity.

My name is Sofia Tsenikli and I’m campaign lead within the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC), an alliance of more than 100 non-governmental organisations that work together for the protection of deep-sea ecosystems.

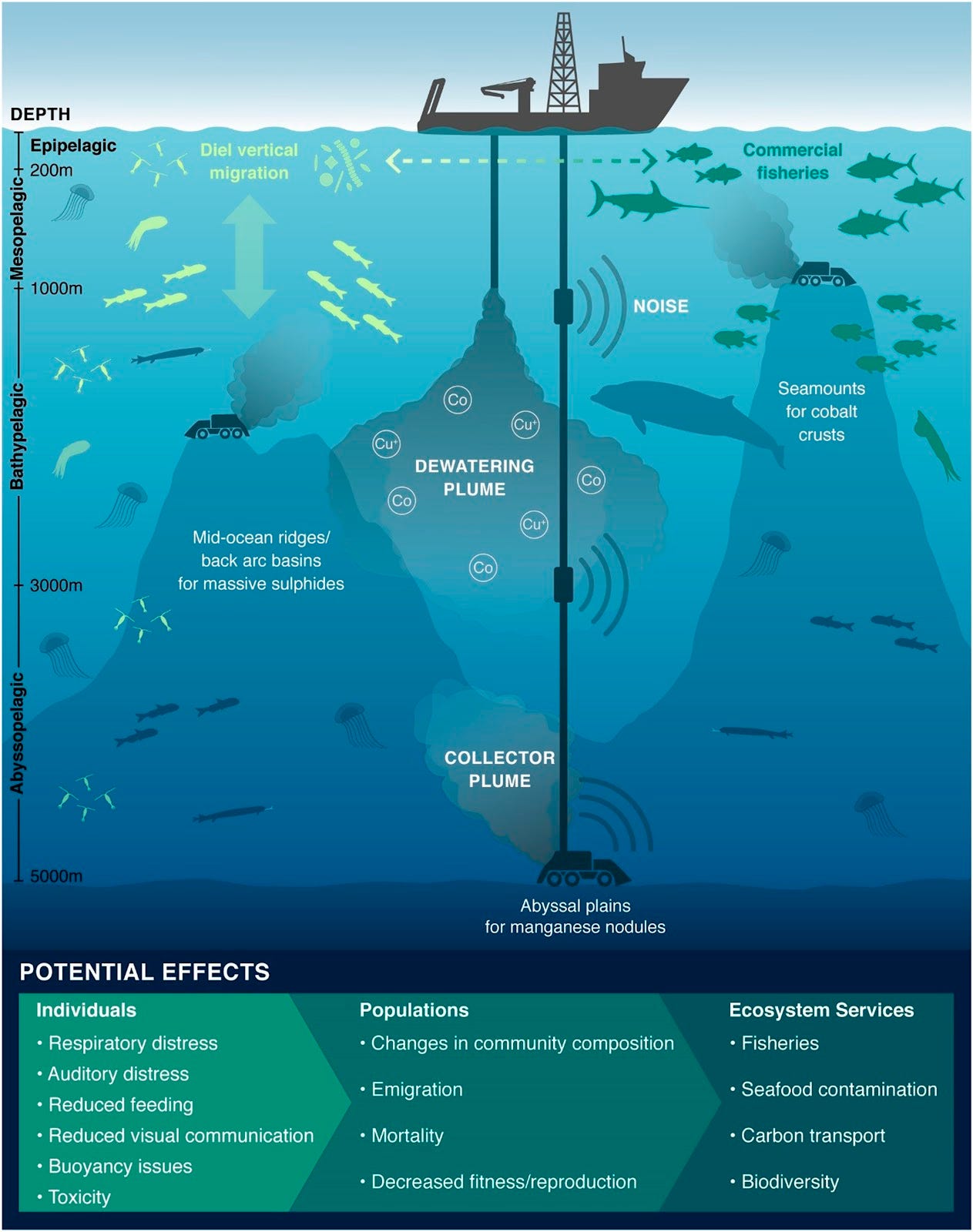

What does deep-sea mining mean and why is it an environmental issue?

There’s a gap in scientific understanding about deep-sea mining. The deep sea is one of the most inaccessible areas on Earth. It’s so far and so deep that species have evolved to survive and thrive in these unique conditions. Recent expeditions have discovered thousands of species that have never been seen before.

DSCC defines deep-sea mining as the process of extracting and often excavating mineral deposits from the deep seabed. The deep seabed is the seabed at ocean depths greater than 200m, and covers about two-thirds of the total seafloor.

[Deep-sea] mining would cause species' extinction before we can even understand not only their ecological role but also the role the deep sea plays in the health of oceans as a whole.

The deep sea acts as a major carbon sink, and mining would severely disturb these crucial processes. If mining companies go ahead, there will be irreversible damage.

Much of the life out there relies on the metal nodules and formations in their environment, allowing them to attach and move around. There is no such thing as taking the metals and allowing life to continue.

We're talking about huge machines that would go down and strip the ocean floor to the surface, introducing light and noise into spaces where that has never happened before. The consequences will affect future generations.

Can you explain the significance of the international meeting in Kingston, Jamaica last month on ocean mining regulations?

Note: Interview took place before the meeting. The outcomes were that no mining code was agreed or adopted. However, since the beginning of the negotiations, another five countries announced their support for a moratorium or pause on deep-sea mining.

The Assembly and the Council of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) met in Jamaica to decide the future of deep-sea mining.

There are currently over 20 countries asking for a precautionary pause or a moratorium on deep-sea mining. There’s also opposition from scientists, even big fishing industry players are urging countries to agree on the pause because the impacts of deep-sea mining in the ocean are unknown.

The UN High Commissioner on Human Rights called for a moratorium this month, stating that going ahead without any regulations would not respect the right of future generations to live in a healthy environment.

The negotiations are critical because the industry would like to see a green light to deep-sea mining happen. There’s a threat that deep-sea mining could start through a legal loophole that would allow these companies to submit an application for mining without any regulatory framework. It’s important to have a moratorium in place and close that loophole so that mining cannot go ahead.

At the Assembly, the organ that sets the strategic direction of the ISA and all 167 member countries can participate and, for the first time in history, discuss a precautionary pause. This marks the beginning of the conversation where countries supporting the moratorium can work towards an agreement on its conditions.

The "mining code," a set of mining regulations, will outline the processes for prospecting, exploring, and exploiting mineral resources. However, due to the legal loophole that remained unaddressed during negotiations, the process of deep seabed mining has now been cast into a realm of legal uncertainty.

What is the timeline for implementing any agreed-upon regulations after the negotiations?

There’s huge questions about equity and benefit sharing, so the regulations are far from being developed. Since there was no agreement for that at the beginning of July, now the loophole is open. But we’re hearing from countries saying that they’re not ready to approve mining activities without proper regulations in place.

This is the moment to put a safeguard with the moratorium, so that we don't sleepwalk into mining because the rules of the ISA are very yielding towards empowering mining. For a licence to be granted, it would need the support of only one-third of the council’s 36 members.

These rules were developed in the 70s when the word “biodiversity” did not even exist. Even if the majority of countries would say no, the regulatory system's complexity could create loopholes that allow mining companies or stakeholders to navigate the objections of most countries and secure approval for mining contracts. The moratorium is the only way forward.

How can the public support the moratorium on deep-sea mining?

More and more people are understanding that once deep-sea mining starts, it can never be reversed. Over the past month, 21 governments, the global seafood sector, 37 global financial institutions, scores of parliamentarians, leading scientists, Indigenous groups and youth groups, have all called for a halt to deep-sea mining.

If you go to our website, you can send a letter to your governments and ministers to support a pause in the moratorium on deep-sea mining. You can also share it on social media with the hashtag #DefendTheDeep.

So Now What Do I Do?

LEARN

Watch: In Too Deep - do we really need to mine the deep ocean?

Attend this webinar on turning your job into a climate career. 30 August.

TRY SOMETHING NEW

Join two major youth networks for a study panel in Hungary on green perspectives on European security. Deadline 20 August.

Submit your film on transforming agrifood systems to the World Food Forum Film Festival before the 25 August.

Generation Climate Europe are looking for their next Head of Operations! Volunteer here.

APPLY FOR THESE OPPORTUNITIES

Activists working on democracy can apply for the Landecker Democracy Fellowship by 6 August.

Submissions for the Youth Carnegie Peace Prize are open! Nominate your project before the 18 August.

Submit your global innovation project to the Social Shifters Challenge by 20 August.

Apply for this cool National Geographic remote nature conservancy and community conservation ‘externship’ by 21 August.

By the way…

The Green Fix is now offering low-cost sponsored slots on the newsletter. Book your slot by emailing wearethegreenfix@gmail.com.

Stay in the loop

You can follow the Green Fix on Twitter @TheGreenFix, Instagram @thegreenfix_ and LinkedIn. You can also connect with Cass Hebron (Editor) on Instagram @coffee_and_casstaways, Twitter @casstaways and LinkedIn Cass J Hebron.

Hey The Green Fix, we are not here to suffer, you're absolutely right. We can all live in abundance and this is not only an esoteric myth. If everyone takes just what (s)he needs, there'd be more than enough for everyone else. Feel free and do what your heart tells you to do. This is always the good way.